ISABEL RUBIO ARROYO | Tungsteno

Architect Francis Kéré recalls that, as a child, he went to school in the city and returned for the holidays to Gando, a small village in Burkina Faso. When the holidays were over and he was saying goodbye, all the women would give him a coin. "In my culture, this is a symbol of deep affection. When I was only seven years old, I was impressed and one day I asked my mother, 'Why do all these women love me so much?' She replied: 'They are helping to pay for your education in the hope that you will succeed and one day come back and help improve the quality of life in the community,'" he says. Eventually he did just that, and in 2022 he became the first black African architect to win the Pritzker Prize, the world's highest award in architecture.

The dream of building better schools

Kéré was born in 1965 in Gando, where there was no clean water, electricity or school, but the community was his family. "Everyone looked after you and the whole village was your playground. I remember the room where my grandmother would sit and tell stories in the dim light as we huddled side by side, her voice inside the room enveloping us, summoning us to come closer and form a safe place. This was my first sense of architecture," he recalls.

As Gando had no school, at the age of seven Kéré went to live with his uncle in the city to study. In Tenkodogo, a city in Burkina Faso with a current population of around 60,000 inhabitants, he attended classes in a room made of concrete blocks with no ventilation or light. Trapped for hours in that extreme climate with more than 100 classmates, he vowed to one day make schools better, according to the Hyatt Foundation, which awards the Pritzker Prize.

Kéré, who later travelled to Berlin on a vocational carpentry scholarship and graduated in architecture, now believes the ideal is to have classrooms where "you can sit, have light that is filtered, entering the way you want it to, across a blackboard or on a desk." "How can we take away the heat coming from the sun, but use the light to our benefit? Creating climatic conditions to give basic comfort allows for true teaching, learning and excitement," he adds.

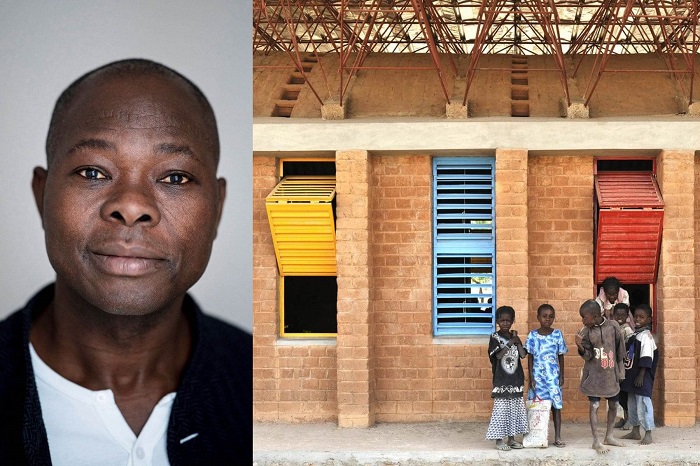

Francis Kéré set up a foundation to raise funds to build a school in his home village. Credit: TED

Sustainable architecture in lands of scarcity

In 1998, the architect created the Kéré Foundation to build infrastructure in his homeland that would benefit future generations. His first building was a school for his village. The Gando Primary School, built in 2001 using handmade elements, won him the Aga Khan Award for Architecture in 2004. The architect decided to strengthen the local clay with cement to make bricks that would draw in cooler air and let the heat escape through a high, wide, cantilevered roof. This ensured that the classrooms were well ventilated.

The architect went on to design other schools, educational centres, housing, medical facilities and public spaces in Burkina Faso, Kenya, Mozambique and Uganda. His buildings often feature double ceilings, indirect lighting and shaded chambers, as opposed to conventional windows, doors and columns. Among his most ambitious projects, the Hyatt Foundation highlights the Burkina Faso National Assembly, which to this day "remains unbuilt amidst present uncertain times." This stepped and lattice pyramidal structure is designed to accommodate a 127-seat assembly hall in the interior. Other significant works include the Xylem pavilion at the Tippet Rise Art Centre in Montana, USA, and the Léo Doctors' Housing and Opera Village in Burkina Faso.

His architecture is "sustainable to the earth and its inhabitants, in lands of extreme scarcity." So says the Hyatt Foundation, which notes that his creations in Africa "have yielded exponential results, not only by providing academic education for children and medical treatment for the unwell, but by instilling occupational opportunities and abiding vocational skills for adults, therefore serving and stabilising the future of entire communities."

Aerial view of Xylem, the Tippet Rise Art Centre pavilion, designed by Kéré. Credit: Iwan Baan

In search of quality, luxury and comfort

"I am hoping to change the paradigm, push people to dream and undergo risk. It is not because you are rich that you should waste material. It is not because you are poor that you should not try to create quality," says Kéré, who has been a visiting professor at the Harvard University Graduate School of Design and the Yale School of Architecture. He believes that everyone deserves quality, luxury and comfort: "We are interlinked and concerns about climate, democracy and scarcity are concerns for us all."

The Burkina Faso National Assembly is one of the architect's most ambitious projects. Credit: Kéré Architecture

His work has spread globally and includes temporary and permanent structures in Denmark, Germany, Italy, Switzerland, the UK and the United States. All of these creations have won him numerous awards, including the BSI Swiss Architectural Award, the Arnold W. Brunner Memorial Prize from the American Academy of Arts and Letters and the Thomas Jefferson Foundation Medal in Architecture, as well as the Pritzker Prize. This last award recognises his narrative that "architecture can become a source of continued and lasting happiness and joy."

· — —

Tungsteno is a journalism laboratory to scan the essence of innovation.