ISABEL RUBIO ARROYO | Tungsteno

Nowadays, we live connected to the Internet 24 hours a day. Although everything seems to indicate that we are moving towards an increasingly wireless world, our Internet connections actually depend on thousands of kilometres of undersea cables that crisscross the oceans of the entire planet. How does this infrastructure work and how important is it for us to be able to use Google, Facebook or WhatsApp almost anywhere in the world?

Currently, 98% of international internet traffic flows through undersea cables, according to Google data: "A vast underwater network of cables crisscrossing the ocean makes it possible to share, search, send and receive information around the world at the speed of light." These cables are made of optical fibre. Theresa Bobis, Regional Director Southern Europe at DE-CIX, says: "They are not too thick, but inside there are hundreds of filaments the thickness of a human hair and, of course, they are protected with layers of different materials."

Thousands of kilometres of undersea cables

Transatlantic cables began to be installed more than 150 years ago for the telegraph network. At the end of the 20th century, the deployment of fibre optics brought about a real revolution in the implementation of this type of cable. Today they connect distant continents along the ocean floor and are "all around the globe," according to Bobis.

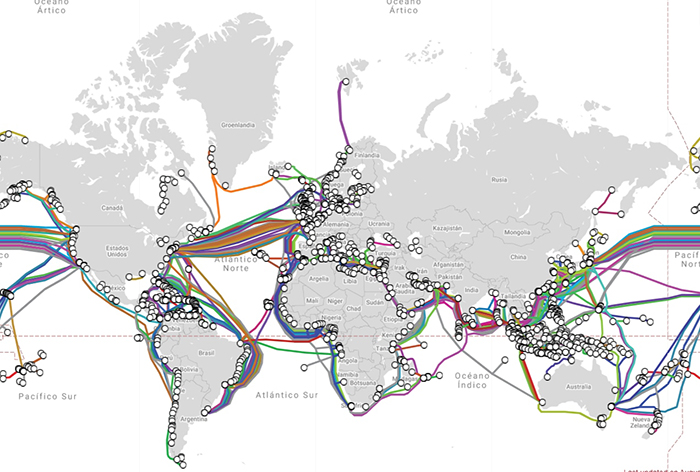

In total, "there are more than 420 underwater cables around the world totalling about 1.3 million kilometres." Some interactive maps show all the undersea cables that are deployed around the world. One example is the Submarine Cable Map, a website that provides data on when each cable began transmitting data, its length and the companies that own it.

There are more than 420 underwater cables around the world totalling about 1.3 million kilometers. Credit: Submarine Cable Map.

Southern Europe alone has "connections with 45 underwater cables, ten of which connect to Spain and nine to Portugal, with another six in the process of being deployed," according to Bobis. Half of these new cables will also reach the peninsula, as the expert points out. For example, one being installed by Google and called Grace Hopper will connect the United States with the United Kingdom and Spain.

From anchors to earthquakes: how undersea cables break

Despite the fact that these cables are increasingly using more modern technology and are more resistant, they do occasionally break. Most damage to undersea cables comes from human activities such as fishing and anchoring, according to TeleGeography, a telecommunications market research and consultancy company. "You might have heard that sharks are known to bite cables, but bites like this haven’t accounted for a single cable fault since 2007," the company says.

In recent years, various researchers have tried to use these underwater cables to detect and predict earthquakes, but in fact it is seismic movements themselves that are one of the main enemies of these cables. A major earthquake in 2006 in southwest Taiwan ruptured eight such cables, affecting several Asian countries. Repairing undersea cables is costly and time-consuming. When they break, a telecommunications operator has to find the location of the failure point, bring the damaged part to the surface and replace it with a new length of cable.

Google's new undersea cable will connect the United States with the United Kingdom and Spain. Credit: Google.

Avoiding breakdowns is important for a robust and reliable connection virtually anywhere in the world. These cables are, in Bobis' words, "indispensable" for transmitting large amounts of data with very low latency. "Today, having a reliable, resilient, high-capacity network is more important than ever, especially as we face a new digital normal with the COVID-19 crisis," said Google Cloud.

Although undersea cables span the oceans, in reality all these connections do not end at the coast, as Bobis explains. They continue over land to link to "data centres, which form the physical space for hosting data, or interconnection points, which are convergence points for content networks, internet service providers and other companies." In other words, while undersea cables "are a fundamental part, they are only one of the links in the Internet ecosystem."

· — —

Tungsteno is a journalism laboratory to scan the essence of innovation. Devised by Materia Publicaciones Científicas for Sacyr’s blog.