Covadonga Betegón Biempica got her degree in industrial engineering at the ETSII in Gijón and her industrial engineering PhD at the University of Oviedo. She is also a professor at the Construction and manufacturing engineering department since 2007.

Her research focuses on metal elastic fracture and elastic-plastic fracture, micromechanical fracture models, finite element method modelling of the physical response of various types of materials, and advanced structural calculus.

Covadonga develops calculus numerical models to determine when fracture of a large-sized metal component happens.

Her field of study has always centered on how metals behave when fractured. That is, how metal elements or structures with a previous fracture behave, and what specific conditions can make that fracture bigger and break the element altogether.

Up to date, she has participated in more than 20 research projects financed by public organizations -in more than half of them as the principal investigator-, she has written more than 50 scientific articles in indexed publications, participated in more than 40 technology transfer partnerships with companies, and directed six PhD dissertations.

“What we do is develop behavior models that reflect the underlying physics of the fracture in large elements, analyzing their behavior at an almost microscopic level. We then elaborate equations based on this microscopic behavior and transfer them to the macro”, explains Betegón.

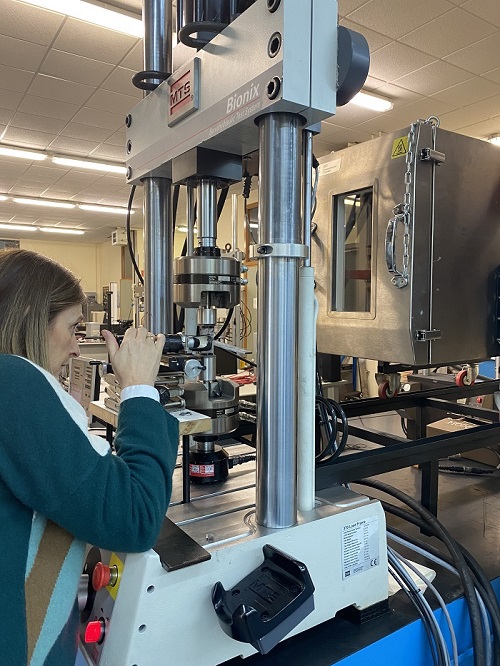

To study alloys, they perform a series of analyses to characterize the material and determine what can cause breakage. Usually, this happens through microscopic porosities that keep growing and cause a fracture.

“Our interest is focused on test runs to characterize all the parameters that describe that process. Then, through models that gather that information we can apply them to structural elements. This what we sometimes call a “virtual test”, explains Covadonga. “Analyzing the rupture process at a microscopic level lets us know which microstructures are more severe or less”.

Covadonga Betegón is now working on how these metals behave when mixed with hydrogen. Hydrogen atoms go into contact with the metal and break it. Normally, they test on deposits, pipes, factory components, etc.

For many people, making hydrogen-resistant materials is a long-term goal.

“What usually happens is that micro tears form and grow larger due to strain, especially if there is a manufacturing defect. When applying high forces too”, explains the researcher.

Understanding the physical phenomenon lets us act in advance and create more resistant materials.

“We also want to find out what causes breakage at an atomic level in the case of rocks. We are interested in rocks that break easily, for excavation purposes at least, to make the process more energy efficient. We want to see the micromechanism in a crystal structure”, affirms this researcher from Asturias.

Project on batteries

In addition, this research team is also working on obtaining the permissions from the National Research Plan for a project related to car batteries for the Universidad de Oviedo.

If a lithium-ion car battery receives damage, it can short-circuit and potentially cause a fire.

“That short-circuit is caused by mechanical reasons, because some battery separators break, and we want to study in some way how batteries behave under impact testing on a cell. We want to find out how we need to place batteries to prevent fires from happening. This research could also be extended to all types of batteries that store energy”, says Covadonga.

Industrial engineering and women

Covadonga thinks her experience as an industrial engineer was not a particularly difficult one. “Whenever I’m giving a talk, I try to encourage girls to sign up for these degrees. I have had the same kind of difficulties as in any other profession. When I was in university, we were only two girls in my class, that is rare.

But it is even more strange that 40 years later, women studying engineering degrees are still a minority.” Some engineering degrees have a 25% women presence, but in computer engineering that percentage is even lower (10%).

“I am an engineer by chance. I can’t brag of having an early calling. I just chose that degree because I liked mathematics and physics, and the universities in my city didn’t offer those programs. Not having many other women classmates wasn’t a conditioning factor for me, I didn’t take it as an obstacle or a challenge to beat”, she concludes.