ISABEL RUBIO ARROYO | Tungsteno

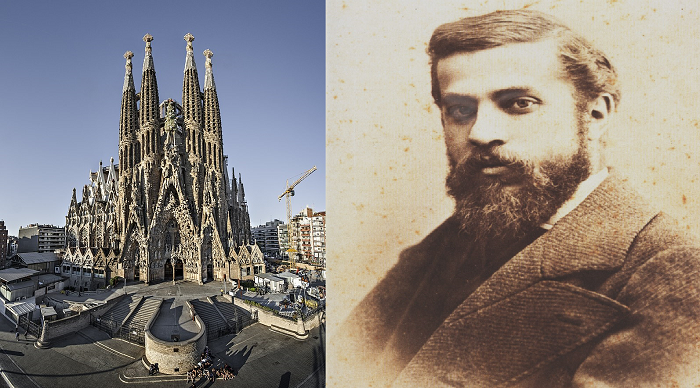

Antoni Gaudí i Cornet, the greatest exponent of Catalan modernism and one of the most emblematic architects of the 20th century, had a great power of imagination. In fact, instead of planning his works on paper, he shaped them directly into 3D models with a wealth of detail. We analyse what inspired him to give life to emblematic constructions that are now World Heritage Sites, such as Park Güell, Casa Batlló and the crypt of La Sagrada Familia itself.

A genius of three-dimensional creation

The architect was born in Reus, a Spanish municipality in the province of Tarragona, in 1852. Coming from a family of boilermakers, he acquired a special ability to work with space and volume while helping his father and grandfather in the family workshop. His great creative capacity and his facility for conceiving space and volume would lead him years later to become a genius of three-dimensional creation.

"I have that quality of feeling, of seeing space, because I am the son of a boilermaker. The boilermaker is a man who, with a surface, forms a volume; he sees the space before he begins to work," said Gaudí himself. The architect used to design his works mentally, rarely choosing to sketch them on plans. He preferred to recreate them directly with three-dimensional models in which he moulded every detail. In his architecture, he also integrated a multitude of artisanal techniques, which he himself mastered: from ceramics and stained glass to iron forging and carpentry.

While studying architecture in Barcelona, he worked as a draughtsman to pay for his studies. Despite being an erratic student, he already stood out for his unique creations. "I do not know if we have awarded this degree to a madman or a genius; only time will tell," said the director of the School of Architecture at the University of Barcelona, Elias Rogent, when Gaudí finished his studies in 1878. And time did eventually provide the answer: his architecture was unique and prodigious. After setting up on his own in an office in Barcelona, he left a great architectural legacy with works such as the Park Güell, the Palau Güell, the Casa Milà (La Pedrera), the Casa Vicens, his work on the Nativity façade and the crypt of the Sagrada Familia, the Casa Batlló and Colonia Güell’s Crypt.

The architect used artisanal techniques such as ceramics, stained glass, iron forging and carpentry. Credit: Construction Board of the Expiatory Temple of the Sagrada Familia.

An attentive observation of nature

Gaudí was the creator of an architectural language that is difficult to label. In a context in which many architects favoured achromatic spaces with straight lines, he opted for a multitude of colours and curved shapes. If his works are characterised by anything, it is by a constant search for inspiration in nature. As he himself stated, "the great book, always open and which we should make an effort to read, is that of nature; the other books have been derived from it and also contain the mistakes and interpretations of men."

During his childhood, health problems meant that Gaudí spent long periods of time in repose, contemplating nature for hours on end and treasuring its secrets. Allegories of plants, animals, movement and even climatic phenomena are present in creations such as Park Güell and La Pedrera. "Gaudí looked at how nature overcomes gravity and what forms are the most resistant; what is the shape of a cave, a mountain, the shores of a lake, termite mounds, anthills, the lairs created by animals that, like man, live in society...", says the Cervantes Institute.

Gaudí conceived buildings in a holistic manner, taking into account structural, decorative and functional issues. An example of this is the extension and renovation of the Casa Batlló, popularly known as the house of bones, the house of masks, the house of yawns or the house of the dragon. In addition to decorating it, he redesigned the façades and interior courtyards to let more light into the interior. For Gaudí, the architect is "the synthetic man, who sees things clearly as a whole before they are done, who situates and connects the elements in their plastic relationship and at the right distance, like their static quality and polychrome sense."

Gaudí completely redesigned the façade of Casa Batlló to allow more light into the interior. Credit: Casa Batlló.

The withdrawal of the celebrated architect

In addition to his professional career, the architect's social life changed over time. While in his youth Gaudí frequented theatres, gatherings and concerts, years later, at the height of the splendour of his work, he stopped making these plans. According to the Casa Batlló website, the architect "went from looking like a young dandy with gourmet tastes to neglecting his personal appearance, eating frugally and distancing himself from social life while devoting himself ever more fervently to a religious and mystical sentiment."

On 7 June 1926, while making his way to the Sagrada Familia, as he did every evening, Gaudí was knocked down by a tram and seriously injured. No one suspected that the unconscious dishevelled 74-year-old was the famous architect, who died three days later. Gaudí was buried in the Chapel of Carmen in the crypt of the Sagrada Familia. Hundreds of people gathered on the esplanade of the basilica to bid a final farewell to the emblematic architect who marked a before and after in Modernisme. He himself knew that his work was innovative, as he said during his lifetime: "My ideas are of an indisputable logic; the only thing that makes me doubt is that they have not been applied before."

· — —

Tungsteno is a journalism laboratory to scan the essence of innovation. Devised by Materia Publicaciones Científicas for Sacyr’s blog.