Leonardo da Vinci is considered one of the most prolific artists, inventors, sculptors, writers and even anatomists of the Italian Renaissance. In addition to creating works of incalculable historical value such as the Mona Lisa and the Vitruvian Man, he was a pioneer in the architecture and urban planning of his time. Five hundred years ago, he devised an ideal city which, in some respects, is not so different from today's cities. His aim was to put an end to health problems, create clean urban spaces and facilitate the transport of goods.

A city to curb the spread of disease

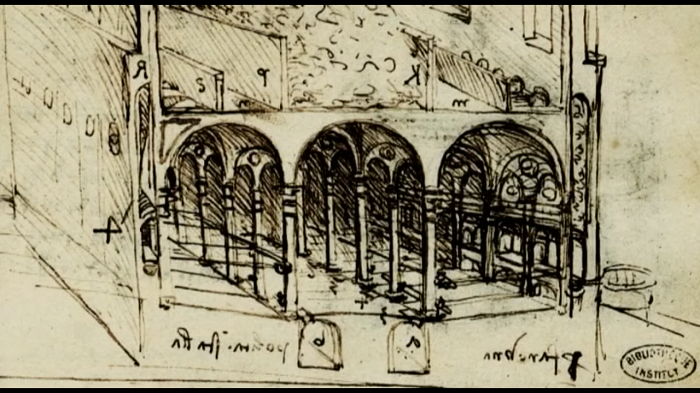

Da Vinci's idea of the ideal city, sketched in some of his notebooks such as the Paris manuscript B and the Codex Atlanticus, emerged after an outbreak of bubonic plague struck Milan and killed nearly a third of the city’s population. "With his scientific instincts, Leonardo realised that the plague was spread by unsanitary conditions and that the health of the citizens was related to the health of their city," wrote Walter Isaacson in his biography of Da Vinci.

Precisely to prevent the spread of disease, the artist set out to create a city with better communications, services and sanitation. "Leonardo wanted a comfortable and spacious city, with well-ordered streets and architecture," explains Alessandro Melis, Principal Lecturer in Sustainable Cities at the University of Portsmouth, in The Conversation. For Da Vinci, the ideal city should have "high, strong walls", as well as "towers and battlements of all necessary and pleasant beauty", a sacred temple and "the convenient composition of private homes".

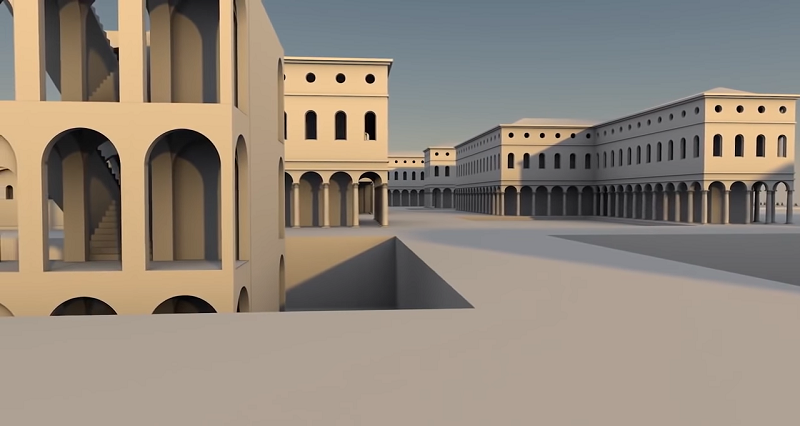

Da Vinci designed an ideal city to improve communications and prevent the spread of disease. Credit: Ideal Spaces Working Group.

A layered city

Unlike the cities of the time, Da Vinci dreamed of a city built on several levels linked by vertical staircases. Melis stresses that this design, which is now common in high-rise buildings, "was absolutely unconventional at the time". "Indeed, his idea of taking full advantage of the interior spaces by positioning flights of stairs on the outside of the buildings wasn’t implemented until the 1920s and 1930s, with the birth of the Modernist movement," says the professor.

Da Vinci envisioned a city in which the upper layers, reserved for the nobility, would have palaces and well-ventilated streets along which to stroll. The lower ones would be for the common people and would be used for trade, transport of goods or industry. "Wagons or other similar things ought not to go in the upper streets, rather, those should be only for gentlemen," Da Vinci himself wrote.

Although some of these features did exist in Roman cities, Melis claims that there had never before been a modern compact multi-level city that was technically so thoroughly conceived. Da Vinci also proposed that the width of the streets should match the average height of the adjacent houses, Melis says: "A rule that is still followed in many contemporary Italian cities, to allow access to the sun and reduce the risk of earthquake damage.”

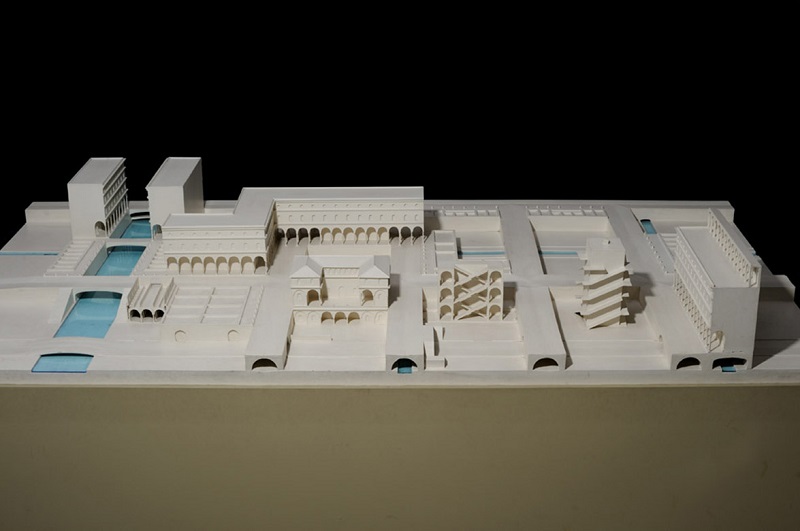

Da Vinci envisioned a city with different levels in which the streets were well ventilated. Credit: National Museum of Science and Technology Leonardo da Vinci.

Canals for goods and sanitation

After studying the canals of Milan, Da Vinci wanted to use water to connect the city as a circulatory system—like that of the human body. To achieve this, he designed artificial canals throughout his ideal city. In principle these conduits, regulated by locks and basins, would facilitate the navigation of ships inland and the transport of goods.

They would also be of vital importance in keeping the city clean. "You will want to take a river that runs briskly, so that it will not corrupt the air of the city, and this will also be convenient to use for cleaning the city frequently," wrote Da Vinci, as reported in the scientific journal Engineering & Technology. In theory, this water network would not remain stagnant thanks to a system of hydraulic pumps.

Da Vinci drew several sketches of what the ideal city would look like, which were never built. Credit: Leonardo da Vinci National Museum of Science and Technology.

Da Vinci's ideal city encompasses some of his talents as an artist, architect, engineer and inventor. Although it was never built, some of his ideas still have relevance today and remain central to urban planning projects. "Many scholars think that the compact city—built upwards instead of outwards, integrated with nature (especially water systems) with efficient transport infrastructure—could help modern cities become more efficient and sustainable," concludes Melis.

· — —

Tungsteno is a journalism laboratory to scan the essence of innovation. Devised by Materia Publicaciones Científicas for Sacyr’s blog.