ISABEL RUBIO ARROYO | Tungsteno

Ever since Neil Armstrong became the first man to set foot on the moon on 20 July 1969, one of mankind's greatest challenges has been to study space and the conditions of life without gravity. The International Space Station has become a floating scientific laboratory. Of the more than 3,000 experiments conducted there, we take a look at the most striking ones and their findings.

One twin in space and the other on Earth

Scott Kelly watched the Apollo 11 moon landing with his family on television. More than four decades later, in 2015, he became the first American to spend almost a year aboard the International Space Station. NASA aimed to study how the human body adapts to prolonged periods in space. To do so, it analysed how the trip affected Kelly’s health by comparing it with that of his twin brother, Mark Kelly, also an astronaut, but who stayed on Earth.

All the findings have been published in the renowned journal Science. Among the most surprising, the researchers cite changes in the length of his telomeres. According to NASA, "telomeres protect our chromosomes, as plastic handles protect jump ropes." But while their length tends to shorten as we age, in space Kelly's telomeres lengthened. However, upon returning to Earth, they returned to pre-flight averages in a short time.

In addition to some changes in gut microorganisms and DNA damage from exposure to radiation outside Earth's atmosphere, his body mass decreased by 7% in space. "This is likely due to increased exercise and controlled nutrition while on his mission, but he also consumed about 30% fewer calories than researchers anticipated," says NASA. Kelly also experienced some ocular changes. Two-thirds of astronauts return from long-duration space missions with myopia, according to a paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Society of Radiology. This is theoretically caused by changes in the cerebrospinal fluid—found in the brain and spinal cord—due to the lack of gravity.

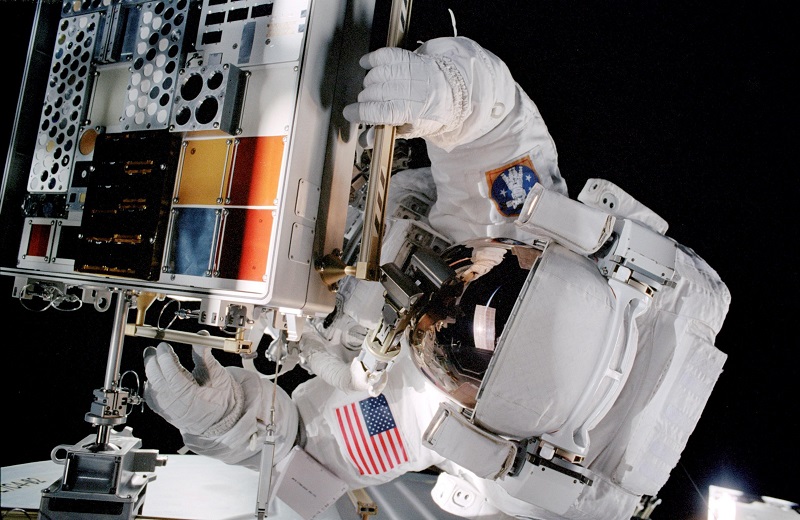

Astronaut Scott Kelly was the first American to spend nearly a year aboard the International Space Station. Credit: NASA.

Flies, mice, spiders and other animals in orbit

Laika the dog was the first terrestrial living creature to orbit the Earth. She did so aboard the Soviet spacecraft Sputnik 2 on 3 November 1957. But years earlier, other animals had already reached space on suborbital flights—those designed to leave the Earth's atmosphere, but without making a complete orbit around the Earth. The first such case involved fruit flies, which the United States sent up in 1947 aboard a captured V-2 rocket designed by Nazi Germany. In less than 200 seconds (just over three minutes), they reached an altitude of approximately 110 kilometres before returning to Earth in a parachute capsule.

These insects have returned to space on more occasions and are also common in genetic research lab. This is because "people and fruit flies are surprisingly alike," according to biologist Sharmila Bhattacharya: "About 77% of known human disease genes have a recognizable match in the genetic code of fruit flies, and 50% of fly protein sequences have mammalian analogues."

Their small size makes them ideal for competing with other biomedical research experiments. As a paper published in Nature notes, "thousands of fruit flies can be housed in a small cassette, similar in size to a deck of cards." In recent years, researchers have studied why these animals have compromised immune systems when reared in space or how their cardiovascular system is affected.

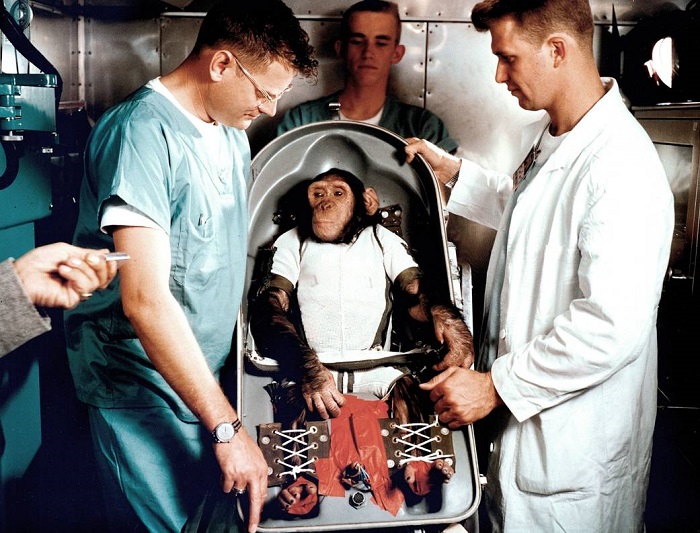

Many other animals have been sent into space. In 1949, the rhesus macaque Albert II became the first mammal to fly into space. In addition, experiments have been conducted with turtles, mice, cats, spiders, frogs and even fish. Special mention should be made of tardigrades, also called water bears. These microscopic organisms can survive several days of exposure to the vacuum, freezing cold and intense radiation of space.

Since 1949, many monkeys and apes have flown in space. Credit: NASA.

Microbes that survive years in space

There are also some bacteria that can survive years in space, outside of a spacecraft, according to research published in the journal Frontiers in Microbiology. Japanese researchers deployed colonies of two bacteria—Deinococcus aerius and Deinococcus radiodurans—of different thicknesses on the outside of the International Space Station. After 1,126 days exposed to the elements, the former did not withstand the experiment. But the D. radiodurans with a thickness of 0.5 micrometres showed similar viability to those grown on Earth. The bacteria most exposed to the outside had died and acted as a shield for the internal bacteria. One of the aims of this research is to test the viability of panspermia, the hypothesis that microbial life could have travelled between planets.

There are many other experiments underway to observe how microbes behave in space. The BioAsteroid project, sponsored by the European Space Agency (ESA), studies whether microbes growing on the surface of rocks can gradually break them down and extract useful minerals and metals. BioAsteroid researcher and professor at the UK Centre for Astrobiology at University of Edinburgh, Charles Cockell, stresses that "microbes have been mining elements for three and a half billion years, long before humans came along."

"Civilisation is built on elements that have been dug out of the crust of the Earth," he says. All these elements have been used throughout history to create a variety of machines, from spacecraft and mobile phone to computers. The potential of these organisms to create other devices is still unknown. As NASA remarks, "perhaps in the future, humanity will have space rocks, and of course microbial miners, to thank for space colonies and new technologies."

· — —

Tungsteno is a journalism laboratory to scan the essence of innovation. Devised by Materia Publicaciones Científicas for Sacyr’s blog.